CHANGE AND DIVERSITY IN POST-WAR SPRINGFIELD

The neighborhood had become more diverse by the late 1800s. Archaeological finds from this time illustrated how different social groups displayed status and what material things they chose.

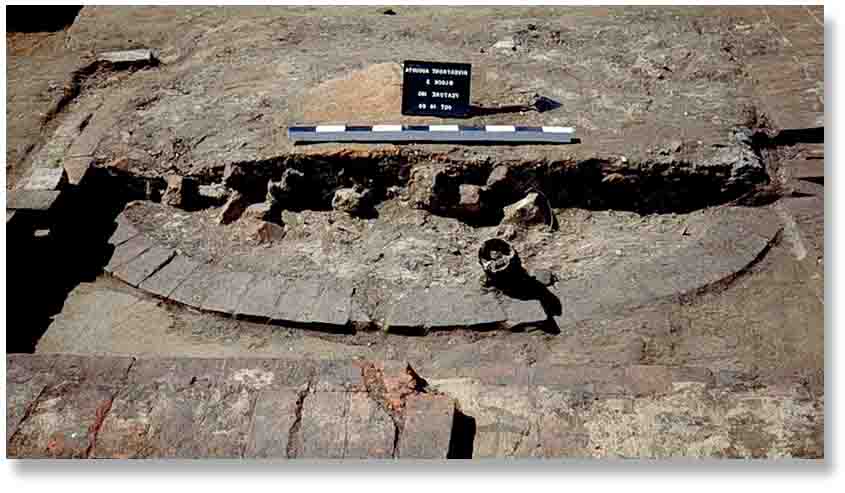

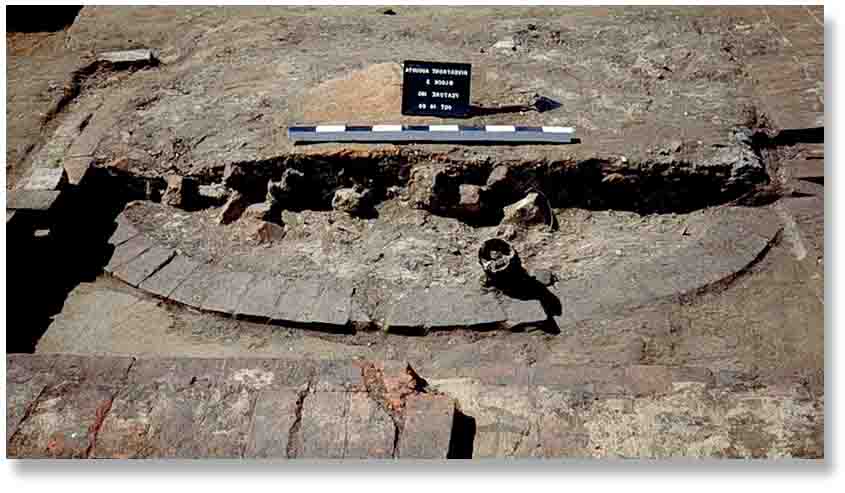

(Above) Abandoned Late Nineteenth-Century Well and Brick Foundations Discovered at the Riverfront Augusta Site. (Source: New South Associates).

By the late 1800s, Springfield had become absorbed into Augusta and had started to take on characteristics of an urban area. Substantial brick structures, larger than any antebellum buildings, had been built and were more numerous, elaborate, and ornate. The architecture showed the influence of Euro American traditions. Denser settlement, larger buildings, and tenement life were also part of the urbanization process.

Archaeological excavations in Augusta have demonstrated important differences in the houses and house lots associated with the city’s African American and European-American residents. A study for the planned extension of St. Sebastian Way discovered that a section of the 1400 blocks of Jones and Broad streets had been taken over and made a housing development during the late 1800s. The development included large, two-story houses on Broad Street, which would contain “every modern luxury and convenience.” In contrast, houses built on Jones Street were one-story “cottages” that cost a third or less than the houses on Broad Street. The smaller houses on Jones Street were inside the Springfield boundary in locations that were traditionally occupied by African Americans and working class European-Americans. Therefore, the new development retained the customary racial and class separation of the 1400 blocks.

Analysis of the site indicated that in addition to the houses having different sizes, the lots were developed differently. Along Broad Street, landfill was used to raise the house lots above the level of the ones on Jones Street, which created a physical and symbolic difference. In addition, the Broad Street houses occupied larger lots, measuring about two and half times as deep as the ones on Jones Street, and the Broad Street lots were separated by clear boundaries that were indicated on maps of the time. The smaller houses on Jones Street were built on a single property without separate yards associated with them. These differences probably reinforced people’s social positions with respect to one another.

House yards at the Riverfront Augusta site showed other differences that might be due to class and ethnicity. Yards associated with European-American households were formally organized around a few permanent structures such as a house, brick drains, brick wells or cisterns, and servant's housing. In contrast, the yards of African American households were more loosely arranged and also contained more pits and activity areas. Archaeologists interpreted this as evidence that African American households used outdoor space more often than European-American residents and also that many of the activity areas were used casually and for shorter periods of time.

The ceramic dinnerware associated with the late 1880s houses suggested other differences in lifestyle. European-American households owned more expensive ceramic tableware than the African American households. However, comparing an African American servants household and a working class tenement at Riverfront Augusta indicated that the servants spent about equally on bowls and plates while the tenement household spent more on bowls than plates. This finding suggested continuation in African American culinary traditions but also implied that status and lifestyle differences existed within the African American community.

African American life in Augusta was diverse. Despite restrictions and prejudice, African Americans managed to develop a rich culture and aspire to various professions and lifestyles. Archaeological finds from the Riverfront Augusta Site suggest that by the end of the nineteenth century, materials things had started to show the differences within African American culture.